|

Luminous orange overalls flap in the strong wind, an egg-yolk sun cracks against the horizon. It’s been a physically tough hike, stumbling over loose rocks, my face caked in black volcanic dust. Atop the cone of Cerro Negro, one of the youngest active volcanoes in Central America, the countdown has begun. All that’s left to do is sit down on my wooden board, lean back, grit my teeth, and hurl down the cone, 0 to 40 km/hr in eight, wild seconds. You can tell the “next big travel thing” by watching the trends of budget travellers, and they’re heading in droves to Nicaragua. The beaches, colonial towns, accommodating locals, and prices are a backpackers dream, along with Bucket List activities like volcano boarding. From the roof of Leon’s cathedral, the largest in Central America, you can see eleven of thirteen surrounding volcanoes surrounding the city. They sit like a chain of pearls on a necklace, and when they erupt, as Cerro Negro did as recently as 1999, it can cover Leon in a layer of fine, ashen dust. Not that it bothers the backpackers at Bigfoot Hostel. When I inquire about the conspicuous absence of waivers for volcano boarding, its affable owner explains some of the legal differences between Nicaragua and the United States. If tourists want to pay twenty bucks for the opportunity to throw themselves off an active volcano, that’s their problem! Even though the volcano is at the tail end of its regular eruption cycle, and could explode any day, Bigfoot is doing a roaring trade, with about a dozen clients of all ages heading out daily, a wooden sleigh in hand, anticipating a Bucket List ride of a lifetime. It took some time to figure out the right apparatus to accomplish such a feat, with everything from fridge doors to second-hand mattresses tested to strike the right balance of speed and relative safety. One thing is certain: while Cerro Negro appears to have soft, sandy steep sides from afar, the granite dust is as sharp as broken glass. Protective overalls, eye-goggles, and remaining seated (as opposed to traditional upright sandboarding) is essential. Wiping out would tear you to shreds. It’s a forty-minute drive to Cerro Negro National Park, and it’s no accident the adventure takes place during late afternoon. The sunsets in this part of the world are atomic, November through June, night after night. We pay a small fee to enter the park, grab our boards, and start the climb up the rear of the ominous looking black pyramid. Once we begin our steep ascent, the wind picks up considerably. Blackened lava from the last eruption sits like an Exxon mess, the thick oil spilled over the countryside. At the back of my mind, I’m well aware that nobody can sandboard faster than an erupting volcano. The loose rocks are sharp but we scramble over them, shifting the awkward weight of our boards from arm to arm. Half an hour later we arrive at the outer edge of the crater to find steaming hot sulphuric ash. You can burn your hand on the ground here, so we keep walking around the lip, a silent prayer that the monster below us remains asleep. With the sun perfectly poised, our guide Gemma explains how to use our feet to break and steer. “Keep the mouth shut unless you want to chew rocks for dinner. Back straight, lean back, and smile for the radar gun at the bottom!” A thin metal sheet is fixed to the bottom of the wood, along with a piece of plastic that increases speed. As I begin the five hundred-metre slide, the grating sound of granite against metal sounds like an engine, revving fast. Rocks and sand attack my goggles, stabbing my lips, sieging my shoes. I’d scream, but it’s wiser to keep lips pursed and board straight (cone-burn awaits those who flip). Active volcanoes have intrigued many a Bucket Lister, but only in Nicaragua will you find one so creatively accessible. Safely on the bottom, the group cracks celebratory cold beers and compares experiences. “Now that’s something to do before you die!” says one backpacker. I certainly agree.

0 Comments

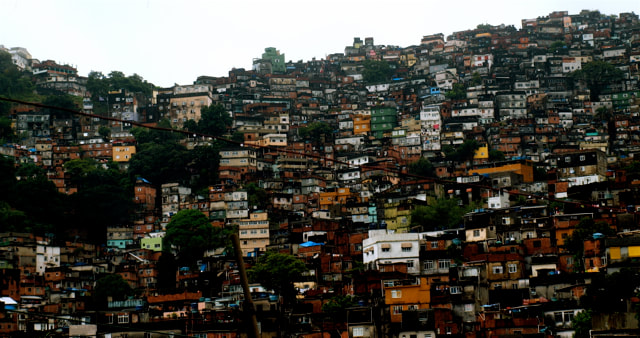

Managua, Nicaragua: The garbage is piled thirty feet high, and walking amongst it, I see four little girls, pushing an old wooden cart of salvaged trash. Soweto, South Africa: I enter a small tin shack where I meet a mother of eight, scratching out her existence, infected with HIV. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: I stroll through the narrow alleys of the biggest slum in South America, keeping an eye out for men with machine guns. Each visit above was part of a tour, an increasingly popular and controversial genre of travel known as Poverty Tourism. Each visit left a profound impact, and each had me wondering whether I was at the forefront of an important new travel trend, or a mutually exploitative human zoo. It is estimated that over 830 million people live in urban slums, most below the breadline, in appalling conditions. I’m going to guestimate that international leisure tourists make up zero percent of that population. An encounter between the two groups is unprecedented and certainly unusual, but is it beneficial? La Chureca is the name of Managua’s city garbage dump, a burning post-apocalyptic nightmare covered in shapeless grey muck. Over 175 families live here, surviving on as little as $1-$2 a day, by turning in plastic for recycling, or salvaging goods of value. Malnutrition is rife, sanitation non-existent, and many kids are hooked on glue. NGO’s are working with the families to improve the situation. Nica Hope helps take children out the dump, to put them in school, teach them skills, and show them a way out. Deanna Ford, an American who founded Nica Hope takes me into La Chureca to show me exactly what she’s up against. The air is acrid, and the flow of garbage trucks constant. On the ground, I walk amongst plastics, bones, rotting food, candy wrappers, broken syringes. Children caked in dirt are barefoot, but two boys play with marbles, like boys anywhere. Deanna takes groups here in the hope they will donate to her cause, sponsor a child, and learn about the realities of this urban slum. “I am aware of tour companies bringing groups in, where they stay in the car, take photos and leave,” she tells me. The human zoo helps nobody, and exploits everyone. Watching Deanna play with the kids, showing them respect, and selflessly doing anything she can to help, I realize that even amongst all this trash, she embodies the most valuable treasure of all: compassion and hope. In Rio de Janiero, Be-a-Local is a tour operator that markets its Rocinha favela tours directly to tourists, mostly backpackers. Several companies offer a similar service, but Be-a-Local is the only one that takes you out the bus and to the top of the slum, letting you walk all the way down. Locals, even police, do not step inside Rocinha. It is just too dangerous, ruled by heavily armed drug gangs, known to explode with bloody violence. With the unspoken blessing of the drug lords, tourists are however allowed welcomed, instructed to put away cameras when they see armed men or boys, and not to wander off. A moto-taxi ride drops us at the top, and as we walk through the crowded, narrow dirt alleys, a new side of Brazil emerges; the real side. Kids playing computer games, little shops catering to the community, men tasked to take away garbage, as there are no municipal services. Rio has over 750 slums, snaking into the surrounding hills, with views of the famous beaches, and luxury high-rise beachfront condos. Be-a-Local donates 40% of the company’s profits to community projects, supporting schools and a day care centre. “Some people say this is voyeurism, but it’s essential if you want to try and understand both sides of the city,” says Laurian Clemence, a traveller on holiday from South Africa. Rocinha, Brazil Over a million people live in Soweto, the largest township outside Johannesburg. Tourists have been coming here for years, visiting Nelson Mandela’s old house, important sites of Apartheid history, the excellent Apartheid Museum. At one point, our mini-van stops and we are allowed to walk amongst shacks of corrugated iron, with aggressive kids peddling all manner of crafts and trinkets. The look of a women inside a shack appears hopeless, the desperation acute. Tourists with cameras do not belong here, in this space, throwing a couple dollars at those given valuable permission to interact with them. While attention is thrown to worthy projects and charities within the township, I cannot but feel this particular stop is an exhibit in some deranged zoo, where poor kids peer out behind rusty fences, amongst bone thin dogs, both begging for scraps. Poverty tours run the gamut of taste and function, depending on the company or organization, the people you’re with, and the place you’re visiting. While some may challenge the ethical value of visiting a foreign slum, there’s no doubt it sheds a fascinating insight on a shocking component of urban reality. In the end, anything that brings people together, across the widest of income or cultural gaps, can only be a good thing. Soweto, South Africa

|

Greetings.

Please come in. Mahalo for removing your shoes. After many years running a behemoth of a blog called Modern Gonzo, I've decided to a: publish a book or eight, and b: make my stories more digestible, relevant, and deserving of your battered attention. Here you will find some of my adventures to over 100 countries, travel tips and advice, rantings, ravings, commentary, observations and ongoing adventures. Previously...

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed