|

It took three, long hours to get to the temple. An hour of that was figuring out which bus to take, negotiating the ticket, and finding directions to the correct platform. Five people were crammed into a seat built for three, and although there were no live animals, there was a freshly slaughtered chicken. It was hot, it was uncomfortable, it was intense, and it was vivid. This is travel, and this is all worth it. I hike up the hill, and there it is, a beautiful stone temple, glowing in the sun. I take a deep breath, pull out my camera, and then I see them. Over a hundred tourists, wearing name tags, following a red umbrella. Ladies and gentlemen: begin the debate! Travellers carry towels, never iron their clothes, and freak out when there’s a schedule. Tourists stay in nice hotels, look forward to going home, and typically pay the set price. Travellers discard guidebooks, tourists clutch them closely to their chests. Travellers need a holiday when they return home, tourists leave home for a holiday. Or vice-versa. The Traveller vs Tourist is a timeless, heated debate. Many backpackers make proud, public announcements so nobody might confuse them with being a tourist. Many tourists seem compelled to sheepishly justify their package vacation, while others would never dream of leaving the comfort bubble of a tour bus. Never mind that both groups are united in the same purpose – to leave their homes and discover something new. And never mind that tourists don’t seem too bothered by the whole debate in general – it’s usually travellers, sitting in a dive bar, scratching the dirt from under their fingernails, scoffing at the thought of seeing anywhere from the comfort of, dare I say it, a brightly coloured tour bus.

At the root of this inane rivalry is the assumption that one experience is better, more authentic, and more valuable than the other. I love it when I meet “real travellers” and the conversation goes like this: Them: “Have you been to Bolivia.” Me: “Yes, I’ve spent three weeks in the country.” Them: Did you go to [insert obscure destination here]. Me: No, I would have loved to, but focused on [insert second obscure destination]. Them: Oh, then you haven’t seen the REAL Bolivia! Me (under my breath): So many stupid people, so few asteroids. Every single one of us is different, and every single one of us will have a different experience, even if we’re in the same place. Further, by definition, anyone who travels can be called a traveller. Some travellers like comfort, peace of mind with their security, being told where to go, and even what to wear. Some travellers like crowded buses, smelly toilets, sleeping in dorms and bargaining for everything. Seriously, they love this stuff! Judging someone by the experience they choose (with little thought to decision-making factors like budget, time, health, or personal preference) is like judging someone because of the colour of their skin, religion, or personal belief. There, I’ve said it. The old debate is nothing more than thinly veiled racism, which, like all racism, is steeped in ignorance, fear, envy, and several ounces of basic stupidity. Still, I don’t see the argument ending anytime soon. As I watched the busload of Japanese name-taggers descend on my (my!) hard-fought temple, having being comfortably dropped off by their luxury air-conditioned bus, I couldn’t help but feel they had missed out on the best part of the journey. And when I told them what I could expect on the long road home, they wondered why anyone in their right mind would put themselves through such an ordeal. It felt rejuvenating to be independent, but I was jealous as hell of their comfort. There’s no right way to apply ketchup to your fries, scratch an itch, or smile at a stranger. While we can always and should learn from the advice of others, there’s also no right way to see the world. There is only your way.

1 Comment

Our 4 months living in Southeast Asia can be broken down into 5 parts:

Thailand was a great start. We jumped into the deep end of digital nomadism, swimming in an exotic culture, and enjoying a slower pace after the frenetic pace of Australia. Bangkok was a sort of purgatory as we waited to visit Bali. Bali was like an overharvested cornfield, a deep disappointment sprinkled with tasty moments. How desperately we needed Hoi An to be different, to be the anti-Bali, to deliver on the promise of why we chose to visit Asia in the first place. And how relieved I am, five weeks later as write these words on the plane back to Melbourne, to reflect that Hoi An delivered. Everything clicked. The warmth of the locals was sincere and inspiring. The food was fantastic. The facilities we found were top-notch. The friends we made were lovely. The house we lived in was the best of any we’d stayed in, the water buffalo abundant, the excursions fun. And most of all, the timing was perfect. Wet season along the central coast of Vietnam officially starts September 1st, the day of our arrival. But the rains only came October 1st, four days before our departure. What September did was dampen the interest of high-season hordes. Hoi An’s lantern-lit night markets, ancient storefronts and coastal attractions were busy, but never overcrowded and unmanageable. It also meant that the locals were even friendlier, flashing their gentle smiles and gifting the kids lollipops. Da Nang, the city that services Hoi An (located 45 minutes drive away along a quiet four lane highway) is exploding. It’s got a lovely long white sandy coastline with resorts and apartments starting to encroach. “This is probably what Rio looked like in the 1960’s,” says Ana. Given its turbulent history, communist Vietnam has embraced modern tourism with a fever, attracting bus loads of Chinese and Korean tourists with mega-resorts sprouting all along the coast, edging closer and closer to Hoi An’s old city. The Four Seasons, the Intercontinental, the Sheraton – it’s all coming in thick and fast, and it’s going to change everything, indeed, it’s already changing everything. The Canadian owner of Dingo Deli – one of our favourite hangouts with its great food and play area for the kids – tells us he was one of the first European families in Hoi An, when the inbound artery of Cua Dao was still a dirt road. This was less than a decade ago. Today, coffee shops and restaurants and tour operators and ubiquitous tailor shops and ATM’s and opulent-looking boutique hotels and mini marts line the paved roads to the Ancient City. In a decade, Hoi An could well become another Bali. And while it felt like we missed the boat with Bali – which must have been incredible a couple decades ago, at least we discovered Hoi An when the going was good. When we could walk beneath the colourful lanterns, scooter through rice paddies, lie in hammocks under coconut trees, shop in busy local markets, and drink strong coffee on the patios. The kids might remember key moments from the photographs that captured our stay, but we’ll remember the general feeling of cultural bliss, contentment, and adventure. Without doubt Hoi An proved to be the highlight of our Big Year, and one we’ll always remember with great fondness. With the pace of modern tourism and the explosive growth of the mass Asian market, going back would probably be heart breaking. I’d never been to Vietnam, and now I deeply regret not putting it into my Modern Gonzo itinerary 13 years ago. It was a different country back then, just emerging from decades of Communist isolation. I’d heard a mixed bag of backpacker’s opinions: some complained they were ripped off every two minutes and hated it. Others said the people were lovely and it was their highlight of SE Asia. And now, so many years later, I heard the same stories, which illuminated the discrepancy. It appears the the big overcrowded cities are intense, and travellers feel preyed upon. Ho Chi Minh (aka Saigon) and Hanoi sound like places far removed from the reggae music, siestas and watermelon shakes we found in Hoi An. It is a small town that repeatedly came up in conversations with friends about places they loved most, and wished they could have stayed longer. Chiang Mai was the other one, and so no surprise we ended up in both. My knowledge of Vietnam, like so many 80s kids growing up in the age of ‘Nam movies, is pretty tainted by the Vietnam War, or what the Vietnamese call the American War. All that’s in the past. Heck, it seems that Communism is in the past, the Vietnamese taking their cue from China – the powerful neighbour that has played a huge influence on Vietnamese culture for millennia – embracing capitalism within the confines of a one-party state. Tourism is embraced and protected. After somehow talking my way out of corrupt police roadblocks in Bali and Thailand, I do not recall any police presence at all during five weeks in Hoi An. Gem’s Rider, where I rented our 130cc Yamaha Nuevo scooter, wanted to keep my drivers license as collateral. “But what about police and roadblocks?” I ask. “Oh, they’d never bother any tourists,” was the reply. Everything here appeared peaceful, the roads were clean, people got about their business (working 7 days a week, I should add). More than once I walked into a store during the hot mid-day siesta to find it abandoned, the products unattended and inviting theft from anyone off the street. It’s why we stopped locking the front gate. If locals are unbothered by petty crime, why should we be? The only relics from the war were the stories we heard from an Israeli we met who was disarming bombs in the countryside for an NGO – “more bombs were dropped on Vietnam than were used in the entire World War II” – and an underwater mortar shell that Ana saw in the bay when she was doing her diving certification. It continued to amaze me that these peaceful, gentle people inflicted a military defeat on the United States superpower, and then swiftly invaded Cambodia to unseat the horrific Khmer Rouge, and then held off an attack from China. The Vietnamese are strong yet peaceful, gentle but unbelievably proud. We Air Bnb’d a house located over the bridge from the Ba Le Market off Cua Dai, in a neighbourhood served by narrow alleyways that can barely squeeze a car. Next door to us was a small holding with banana and coconut trees, and across the road was a modest yellow temple on the shores of a large river. The house was called Mali One, consisting of 4 bedrooms and 4 bathrooms, two upstairs and two downstairs, typically rented individually. We took the whole place, giving Amy her own space and a different area for Raquel’s home-schooling. With temperatures ranging between 28C – 35C, air-conditioners in each bedroom were essential for sleep, and fans aerated the muggy air in the living areas. The shower pressure was great, , we could flush toilet paper, and brush our teeth with tap water. There were roosters next door and across the street, but their crows didn’t destroy us like they did in Chiang Mai. Dozens of geckos patrolled the walls, and fortunately we’d missed the brunt of mosquito season. A giant spider hung out downstairs by the front door, but we pretended not to notice it. On our first morning, discovering the Dingo Deli by chance, we met a Canadian family temporary living in Hoi An with their two daughters, the same age as Raquel and Galileo. We got to know Meredith and Jonathan, Charlotte and Aria well over the next 5 weeks, and shared the joys and challenges that come with schlepping your family around the world. They introduced us to Kahunas – a friendly backpacker’s beach club that welcomed families to swim in their pool and use their beach chairs. No $50 entry fee, no Bali exclusiveness. Having broken in our scooter skills, we could pile onto the long backseat of the Yamaha and cruise the relatively calm streets of Hoi An and its surrounds. Vietnamese scooter driving is as insane, probably more so, than in Bali. Bikes come from every direction, at any time. People bike on the wrong side of the road or on the pavements, using lights when they feel like it, carrying washing machines or mirrors or other bikes on their bikes, honking repeatedly and unnervingly. We saw a couple accidents, and drunk people who could barely stand much less pilot a bike. One hapless duo as so hammered on their bike they literally fell over in the middle of the street. The difference with Bali’s madness is that there was a lot less traffic. Outside of the hectic 4pm to 5pm school hour, the roads were generally calm and the highways basically empty. Ana and I took the bike on a roadtrip to the Hai Van Pass, cruising over mountains and through some of the busier traffic areas in Da Nang. As crazy as the riding and traffic was, it never felt nearly as dangerous and as desperate as in Bali. As a bonus, concrete paths created shortcuts through the green rice paddies that surrounded Hoi An, showcasing water buffalo and farmers in pointy hats accompanied by wonderful feelings of exoticness and travel buzz. I never wore a helmet, and have confirmed that riding a scooter with the warm tropical wind in my hair is as close to nirvana as I can be, more-so when I feel Raquel hugging me at the back, and have Gali holding onto the antennae-like mirror stands in the front. Speeding along the the “water buffalo road” to Kahunas, and zipping about the rice paddies on the bike, comprise my singular best moments of the entire year abroad. Just about every morning I would pop on the bike and ride around the corner – slowly across the road that became more and more flooded – to the Ba Le market. Fresh bananas, mangoes, dragon fruit, watermelon…I’d have to haggle but at 17,000 dong to one Canadian dollar, it was always a bargain. Some ladies ripped me off more than others, my favourite was Miss Huey, who always added a handful of fresh mint, spring onions, basil and other herbs the Vietnamese add to the soups, noodles and sandwiches. Across the road was the white house bakery, where I could buy fresh baguettes and breads, and a little further down, the Hoi An version of Bali’s Everything Shop, although it wasn’t very big and certainly didn't have everything. There were no supermarkets in Hoi An, no 7-11s, no Cocomarts or Pepito Express – and the two stores that sold groceries left no doubt that it was cheaper and a lot easier to just eat out. Meals would cost between 30K – 130K, depending on the type of restaurant, and unlike Thailand or Bali, there were plenty of affordable Western options. Raquel liked her freshly squeezed lime juice, Gali his watermelon juice, and every day the kids would have their Yakult and Milo drinks, along with homemade ice lollies from juice. We made our own smoothies, and although I cooked schnitzel a couple times, we got a lot of take-aways from one-person kitchen restaurants nearby. Visitors to Hoi An typically come for about 2-3 days, rent a bike to cycle in the rice paddies, visit the lantern-lit Ancient Town, check out a few temples perhaps, and pop into a tailor to get a suit, dress or shirt made. Every Friday we’d go to the Chabad – always the only non-Israelis – and those we spoke to were amazed we were actually living in Hoi An. “But what is there to do here?” they’d ask, and we’d say, “not much, which is why we love it.” After having done so much this year, the opportunity to spend days by a luke-warm pool drinking Larue, Saigon or Tiger beer sold cheaper than bottled water while the kids play with new friends to the tunes of vintage reggae is as close to paradise as we can hope for. Of course we got the suits and dress made, it’s the thing to do here, and you’ll struggle to find bespoke tailoring cheaper. On the advice of someone from the Hoi An Expats Facebook group, we ended up at Cloth Shop Sue, where I got a suit, a blazer, 4 shirts and 3 waistcoats, and Ana got a suit, dress, and pants. Shipping wasn’t too expensive, so we sent 26kg of clothes, souvenirs, books, and other stuff we’re trired of schlepping around home to Canada via sea. Hopefully it arrives! In our home was a 2002 copy of Lonely Planet Vietnam, and the country it describes is very different from the Vietnam 16 years later. Hoi An is described as a small but popular town famous for its temples - we only visited one of them, by accident. Our two sojourns were me taking Raquel on the bike to the Marble Mountains, a series of limestone outcrops overlooking flat Da Nang. We took the elevator up to the top and visited a couple cave temples, sweating bullets in the process. After riding 90 km;/hr with Raquel, I’m more confident than ever to get a motorbike! Our second adventure was to the Ba Na Hills, a bizarre kitschy French medieval-style theme park built high in the mountains, and serviced by cable cars. It was expensive and took a while to get to, but the admission price included all the rides, and they’d recently unveiled a stunning “hand” bridge that made world news when it was unveiled a few months before we got there. We went to see a water puppet show, which was quite fascinating, visited Cham Island, which was less so. Amy took the kids on a small traditional boat that looks like a saucer, after which they made stuff with coconut fronds. We visited the Ancient Town a couple times, took the boat on the Ancient Town to let the kids make a wish as they released a floating candle-lantern. We hit pub night where we didn’t fare particularly well but did win a pitcher of beer, and followed that up by a visit to the Dive Bar, which wasn’t a dive bar at all, and watched Jonathan support the local nitrous oxide balloon dealer. With booze this cheap, tourists were more than happy to buy rounds for everyone. For Ana’s birthday, Amy looked after the kids while Ana and I spent the night in a fancy hotel, having dinner and dancing to a samba band (yes, a samba band!) at a place called Soul Kitchen in An Bang. From the layabout couches to the kid-friendly restaurants on the beach, there was just so much to love here. Raquel even took ballet classes on Saturday mornings, with an English teacher who knew what she was doing (in stark contrast to Bali). The expat community heard about us and it’s a small circle – the folks with young kids living in a small town in a strange country. Otherwise, no lost boys in caves or tragic earthquakes, although the ceremonial president of Vietnam did die, not that we (or the rest of the world) heard much about it. A typical day looked like this: 6am - 8am: Wake up, make breakfast, hear about Amy’s evening exploits with the South Africans living in Hoi An teaching English to Chinese students online. 10am – 2pm: Kahunas or playdate 2pm – 4pm: Gali naps, Raquel does school with Miss Amy downstairs, Robin works in Australian Bucket List website/Ana explores/get PADI certified/rides around looking for baguettes. 4pm – 6pm: Kahunas or playdate with Charlotte or bike ride to the water buffalo or or some such thing. 6pm – 8pm: Dinner, shower and bed time. 9pm – 11pm: Monopoly Deal or Netflix or Pub Quiz or Girls Night Out or Book Reading or Sleep. Other memories: The Koi Café, the karaoke clubs, the weddings, the trips to the one ATM machine where you could withdraw 5m dong. The inflatable pool on our upstairs patio, emptying the water over the sides into the banana trees. Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, the Chabad eggplant, hunting for diapers, hunting for new shoes for Gali. The challenging Wednesday night Pub Quiz (the most populous mammal on Earth is not humans!), the Birthday night away in a real hotel and dancing to Samba at Soul Kitchen, the horrendous sound of river frogs, the power failures, the horrendous sound of Vietnamese karaoke, the insanely strong coffee, the kids doing this, the kids doing that… It’s all a blur, and time does fly when you’re having fun. Unlike Bali, where the highlights were crisp because they were fewer and far between, days in Hoi An blended into each other the way we blended the market fruit into smoothies. At the the end of it, when Amy looked after all four kids and we hit the town with Jonathan and Meredith - four parents of four young kids bewildered to have some fun time to ourselves - we realized we’d be sad to say goodbye, and yet if you don’t, months will blend in the same sort of motion blur. It’s just hard to get much done when the going is this good, and it’s the closest we’ve had to a family holiday since we took the kids to Maui in April 2017. For despite what people think, just because you’re travelling, it doesn’t mean you’re on vacation. At least, until you find yourself in a place like Hoi An, the kind of place travellers visit for a few days and end up staying for a few weeks, the kind of place that vindicates your wild, crazy, irresponsible and risky decision to go travelling for a year in the first place.

Living in a country, as opposed to travelling through it, is a form of travel I have long felt missing in my repertoire. My career, after all, has too often involved the ticking off of unique experiences, and then running off to the next destination. After a frenetic 6-month research period in Australia to write my next book, and with my daughter only starting kindergarten at the year-end, it felt like the perfect opportunity to live in a place I've always loved, and in places I've yet to explore. We started with six weeks in Chiang Mai. I first visited the city 2005, and fell in love with it. Unlike the congested, polluted mess that is Bangkok, Chiang Mai was friendly, peaceful and calm, beaming with golden temples, cheap eats, and guesthouses. I returned a few years later to film an episode of Word Travels, and always thought: “If I had to live anywhere in Asia for a while, this would be the place.” With my family and Amy, our own travelling Mary Poppins-assistant in tow, we found a semi-detached house outside of the Old Town on Air Bnb, and prepared to settle into the neighbourhood. The Thai – at least those outside of heavy tourist zones - are just unbelievably, remarkably, authentically warm and gentle people. They love children. They smile a lot. They are 95% Buddhist. We weren’t off the plane for five minutes and felt reassured by the welcoming nature of the culture. . Our house was at the end of a soi, an alley, off a busy road. Everything was so different, so anything-goes, so jarring, so unlike Australia. Like most Thai houses, ours didn’t have much of a kitchen (a gas burner, a fridge, some basic cutlery and utensils). Like most Thai houses, we wouldn’t be able to flush toilet paper down the toilet. The beds were rock hard, the furniture basic, the shower pressure almost non-existent. A rooster crowed directly across from us all through the night (more on the rooster later). There was blessed air conditioning in the bedrooms, and just a fan downstairs. Mosquitoes and flies patrolled the windows and the wonky screen door. Inside the place was clean, but a little rough around the edges, softened each Monday when the cleaner would come and leave it spotless. When we arrived, my wife looked at me like I was a madman for bringing us here. But at least we wouldn’t have to unpack after a few days, and at least we didn’t have anything in particular to do. We could just be. Our street It took us about 10 days to get our bearings, to navigate the wild discrepancies between tourist/rich Thai prices, and local/poor Thai prices. After our careful budget in Australia, we leaned heavily towards to the latter. All that beef in Australia disappeared from the menu in Northern Thailand (unless we wanted to pay $50 for a steak in a fancy mall restaurant). Up here, they love pork, pork and smelly fish, rice, pork and rice, and lots of chicken. Prices for food in the big Tesco supermarket were significantly more expensive than Australia. We splurged on olive oil. Cheap plastic toys from China were triple the price. In fact, everything was more expensive than I anticipated. In the decade since I last visited, Chiang Mai has become a haven for an estimated 3000- 5000 digital nomads – people who can work from anywhere - and Chiang Mai is as good as an anywhere as you’d want to be. A military coup that took place a few years ago in Thailand must be good for business and tourism because the sheer number of visitors and new hotels within Old Town was staggering. Every shop was a guesthouse or tour operator, a massage parlour or restaurant. While we might see one or two westerners wandering about our neighbourhood, once we crossed the old walls into Old Town, gringos were everywhere, still wearing the baggy elephant-imprint pants one can only wear in Thailand without looking ridiculous. At first, we wondered if we made a mistake booking a place so removed from the thick of Old Town, but quickly came to appreciate it. Because we did indeed get to know the community, who embraced us after a couple weeks when they realized we were not the typical transient visitors. We slotted into a lifestyle that was more than just visiting temples, going to overpriced bars and eating pad thai. Although we definitely visited temples and ate pad thai. Temples and Mobikes Getting around was affordable and easy, something we really only appreciated when we arrived in Bangkok, where getting around was difficult and comparatively expensive. Mobike, Chiang Mai’s public bicycle system, allowed us to rent bikes with handy baskets in the front, seemingly perfectly designed for the kids to sit up front. Solar powered and blue-tooth operated through a phone app, the bikes could be left anywhere, so we basically just “borrowed” a few to use and permanently kept them outside our heavy sliding green gate. It cost 10 baht (about 50c) for a half hour, although I got a 200 baht ($10) unlimited use for 90 days pass. My fondest memories of Chiang Mai are riding the streets with Raquel or Gali in the basket, stopping at temples, waving to locals. Chiang Mai is mostly flat, and the Mobikes – at least the orange ones we used and not the wonky silver ones – were super comfortable. We never saw any other kids in the baskets, and neither had anyone else, which is why Gali and Raquel were instant rock stars on the Mobikes. Smiles and laughs and waves came from every direction. For further distances, Grab Taxis is the local Uber, and they eliminated the constant haggle and rip off with tuk tuk drivers and taxi drivers. The fare was always fair, and the drivers gave us no nonsense. What a game changer! We took a few tuk tuks, more for the experience, but between the Mobikes and Grab, we could get around wherever we needed to go. On the last week, I hired a scooter, which was super fun, even if we had to wear a helmet primarily to avoid the bribes we’d have to pay at roadblocks (only foreigners get stopped if they don’t have a helmet). Our underpowered bike didn’t make it up every hill, but we had a fun day lunching by a river, feeling the jungle breeze, and braking for elephants. Raquel only fell asleep twice, on the scooter, in heavy traffic. Raquel and I took a bigger bike for a 90-minute ride to the beautiful Sticky Waterfalls. It was quite the adventure I hope she somehow remembers, racing 100 km/hr through the jungles of Northern Thailand, seated between my legs. One the ladies “Hi-low Lay-dees!” The local Thai ladies were besotted with the kids, especially Gali. We never got their names and would not be able to remember or pronounce them if we did, so we just called them “the ladies.” On our street, upstairs in an old wooden house was an old lady always sewing. She always smiled and waved, and raced downstairs one day to give the kids handmade Thai clothes. We printed out a picture of her and the kids to say thanks. When we said goodbye, she gave the kids teary hugs and some wooden Buddhas. On our corner was the “chicken fried rice ladies”, working in their gritty local eatery a tourist wouldn’t go near. We must have waved and greeted to them at least six times a day. They made us the fine and tasty chicken fried rice that we ate a couple times a week. Then there was the Thai Ice Tea lady, although we all had our favourite Thai tea lady. The Plastic Lady, who provided us with plastic bins and knick knacks and spoke some English. The Pad Thai ladies, another place tourists wouldn’t blink at but made a great 30 baht ($1.50) pad thai. The Market Ladies, the Fruit Lady, the Temple Lady (above) who always cried when she saw the kids, the Pancake Lady, the Ice Cream Lady. We did cook at home a fair amount and realized how much we miss an oven when we don’t have one. We made do with pasta and deep friend chicken and eggs and toast in the morning, although usually had to watch out for the geckos jumping out of the toaster. My wife took a Thai cooking class and came home to make a fantastic Tom Yum soup. It was often more expensive to buy the ingredients than just grab a pad thai. Without eating pork or stinky fish, it says much about Thai cooking that we ate chicken/rice/noodles in some configuration for 6 weeks without getting tired of it. There was a local vegetable market - more friendly ladies - around the corner, along with a Tesco Express and 7-11 (a mini supermarket), and it all amounted to a situation that became dependably convenient – something we again only appreciated when we left Chiang Mai. Pity the fool who messes with this 5 year-old Also around the corner was a gritty local Muay Thai gym – Thai kickboxing. We paid the friendly manager Ratana to give Raquel private lessons on Thursday nights. Ratana and her pretty daughter loved Raquel, who cut the cutest curly-haired figure sparring among sweaty fighters. She learned to keep her fists up, kick, punch and elbow, and survive the massive mosquitoes attacking the gym in the early evening. Ratana took lots of videos, she thought Raquel was just amazing. We hoped the lessons would help burn off some of her energy so there wouldn’t be a prize fight trying to get her to sleep that night. Although we tried hard not to be tourists, of course we did a few touristy things. Art in Paradise is an interactive art museum that blew us away, putting us in the picture with dinosaurs and masterpieces. The kids loved the Elephant Poo Poo Park, where dung is sustainably converted into paper (it's a lot more interesting than it sounds, and in case you're wondering, doesn't smell at all). We visited a massive waterpark called Tube Trek, the Saturday Night Market, which was so much better than the overcrowded Sunday Night Market. The Ginger Farm, where Gali fell into a muddy trench. He had more luck at the Buak Hard Public Park, which had the only decent playground we could find. Of course there were all the amazing temples, and we had a beautiful moment with an elephant on the road without visiting an expensive and dubiously elephant park. We made friends with wonderful locals and expats (and their kids), celebrated birthdays. Along with the rest of the world, we anxiously watched the dramatic rescue of the schoolboys from a cave located a few hours drive away. We joined hundred of Israelis every Friday night for a Chabad feast, and enjoyed the spectacle of the FIFA World Cup in Russia, washed down with tall bottles of cold Singha beer. Next door was a Burmese family who prepared rounded fish balls over burning charcoal, the smell of which reliably wafted through the windows each afternoon. Each night, and often during the day, the loud roosters would get started. If they didn’t keep us awake, they invaded our dreams. We spent long nights lying in semi-sleep thinking about how much we’d love to kill those damn birds. I suppose it was revenge for the sheer amount of chicken we ate every day. Making paper with elephant poo Art in Paradise We brake for elephants The smell of the camphor/citronella mosquito spray. The ants that would snake from the ceiling to the garbage bin in the kitchen. The kids writing with chalk on the patio outside before the daily late afternoon tropical rain would wash their scribbles away. Amy’s ongoing saga with the dodgy dentists of Chiang Mai. The manual washing machine we didn’t use in the back, and the communal washing machines we did down the road. The modern malls and dragon fruit. The homemade ice-lollies with the plastic we bought from the Plastic Lady. To say nothing of Chiang Mai itself, with its bustling markets, and shiny golden Buddhist temples, orange robed monks, crazy traffic, and pungent fish-sauce fragrances. The kids couldn’t enjoy our $15 hour-long massages in the dark but innocent backrooms off the strip next to the Doo Dee Bar, but they sure chomped down the surprisingly good biltong we managed to find, made by a Dutchman, and delivered to our front gate. Warorot Market We could only appreciate how comfortable we’d become in Chiang Mai when we bid our farewells and arrived in Bangkok for 2 weeks. Our first Air Bnb was such an epic disaster we had to evacuate it after a few hours (with a small refund, thanks Air Bnb). Our second last-minute emergency lodging was called the Paradise Sukhumvit, which was as far from Paradise as you can imagine. Our third attempt was modern and clean and on the 29th floor of a condo in Thonglor, which is where you want to be in sticky, smoggy Bangkok, away from the insane traffic and noise and mayhem. A big city means less smiles, and more issues getting around to do anything. The disparity between expensive “normal” restaurants and cheap street food, between normal Thai and rich Thai/expat, is bewildering and excessive. The traffic can often jam you into a single intersection for 15 minutes. Grab Taxi is double the price here because you’re hardly moving. It’s enough to make you want to lock yourself up in a tower with a swimming pool and air conditioning and hardly venture outside. We did take a couple crazy river boats and visited some of the bigger temples, hooked up an amazing indoor play area in a ritzy mall where a hand bag costs more than several month’s wages. Still, Bangkok offered up some wonderful and vivid moments: riding the loud riverboats up the narrow canals (always preferable to the frustrating gridlock in the back of a taxi). The incredible temples and time well spent in the wonderful condo infinity pool above the snarling traffic on Petchaburi Road; a play date with a family from Vancouver; Raquel conquering the monkey bars for the first time in Lumpini Park, seeing a movie where the audience must stand and sing tribute to the King (I'd say more about the King, but in Thailand that can get you arrested). Bangkok, oriental city... We hope Chiang Mai is only the beginning of the amazing experiences to come in Bali and Vietnam (and a side trip to Singapore to see our old dear friends), as opposed to the pinnacle of our Asian adventure. Because if I reminisce about it so fondly after being away from the city for less than a week, memory will likely grow positively and brighter as the months and years pass. My family spent 6 weeks in Thailand. Not travelled in, but lived. It was a culture shock, it was full of big challenges, unforgettable and wonderful moments, lovely people, and everything we hoped it would be. Next up: Bali.

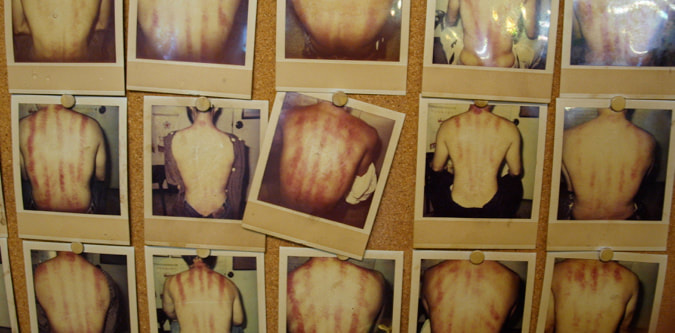

The Fire Doctor of Taipei has coated my back with a brown paste of herbs, covered me with a towel, and spritzed on some alcohol. After lowering the lights, he tells me to be calm, and then lights up the blowtorch. I hear a sound not unlike that of a gas burner being lit, and catch the reflection of flames off a nearby mirror. It takes a few moments to register that the source of the fire is my back, followed by the sudden rush of intense heat. For over a dozen years, Master Hsieh Ching-long has been using open flame to rid the pain. Master Hsieh (pronounced Shay) created fire therapy a dozen years ago after medical training in Beijing, applying his knowledge of traditional medicine, martial arts, and pyromania to invent a powerful treatment for muscle aches and sports injuries. Photos on display in his small clinic depict the doctor with several dozen local celebrities, and he tells me that business is booming. “Not anybody can heal with flame,” says the Fire Doctor. It requires years of martial arts training, so that you can channel your inner energy and use your hands as iron. I’m not sure what this means exactly, but it sounded comic-book cool, and when he demonstrated the above by ripping an apple in half with his thumbs, I knew I was in good hands. Being set alight was my thrill of choice in Taiwan, the “other” China. Officially recognized by only 23 countries, the island nation lives in a constant state of tension with its larger Chinese neighbour, with mainland invasion just a few missiles away. Established in 1949 after the communist revolution, Taiwan’s US-supported economy boomed, its democracy flourished, and today it is amongst the sharpest claws of the Asian Tiger economies. With political rhetoric heating up, many look to the success of Hong Kong as a potential future for the peaceful reintegration of Taiwan and China. In the meantime, I had my own heat to deal with. I was hoping Master Hsieh could use his able hands, scarred with burns over time, to untie the thick plane knots in my back. My treatment would come in three stages. Firstly, he would use heated glass cups to realign the energy. Gwyneth Paltrow popularized this treatment a couple years back when she revealed the source of the circular purple welts on her back. It was only during my second treatment, when the blowtorch was fired up, that my nerves began sweating. The herb paste burns for a several seconds before the good doctor douses the flames with a towel, and massages the intense heat into my skin. “Now for the dangerous part,” he says, in which open flame is applied directly to the skin. Photos of other patients on the wall showed grilled skin, lines like steak on a barbeque. I sit upright, and feel the flame rolled down my back on cotton doused in alcohol. It hurts. A lot. I smell the sickly-sweet scent of skin being scorched. Finally, the doctor uses his vice-grip hands for a deep tissue massage, and signals the end of the treatment. My back is bright red, but thankfully free of burn marks. I step out into the heat of Taipei, my adrenaline ablaze; the stiff muscles from yesterday’s long-haul flight slashed, burned, and cast off into oblivion. Master Hseih Ching-long’s Fire Clinic is located at No.2, Sec. 1, Chenggong Rd., Nangang District, Taipei City 115, Taiwan. Treatments typically last 40 minutes, and cost around $35 per session. Different skin can react to open flame in different ways, and heat bruises are common.

TOKYO, JAPAN. Thousands of cherry blossoms are exploding into life, but I'm not only here to see the colour of Spring. I want to see the Sensoji Temple at twilight, when you can hear the gongs, smell the incense, think about Samurai movies and pretend you're a Shogun. I want to explore the mishmash of neighborhoods, where swish boutiques appear out of nowhere and women walk around with their pet pigs. I want to ride the efficient subways, stacked like a sardine, feeling the white glove of the train pushers. I want chat up the Harajuku Girls, who train in from the subways each Sunday dressed like vampires or goths or Alice in Wonderland. And groove with the Dancing Elvis's in Yoyogi Park, the same guys who have been doing this every week for 20 years, shunning away anyone who tries to join them. I want to stroll around the themed hotels that can be rented by the hour, looking at the sheepish faces of the middle--class couples that emerge from their empty lobbies. And pick up a strange tasting drink from the endless fruity vending machines, that offer treats and hope for just a few yen. I want to shop for $200 melons that I can give to my gracious hosts as a prized gift. And find hole-in-the wall eateries where the bartender does magic tricks, serving $20 beers. I want to visit the Tsukiji fish market in the early house of the morning, the largest fish market in Japan, where frozen and fresh tuna are laid out for quickfire auction sales. And finally, I want to write a wish on an ema tablet outside the Meija Jungu Shrine, so that I'll be able to return to Tokyo next April, and further explore this wonderful, bizarro city. Special thanks to Brad and Tams.

When we last caught up with travel-fanatic Rus Margolin, he had just been to over 100 countries. Well, he just ticked off his 200th. I met Rus at Arctic Watch, one of the highlights on The Great Canadian Bucket List, and the kind of remote shore where rather interesting people wash up. For example, former-bond traders from New York who decide to visit every country in the world. Many years ago, I remember telling a girl in Hungary that I was travelling around the world, and without missing a beat, she asked me: So, what have you learned?” I caught up with Rus for a conversation about travel, experiences, highlights, some places you might not have heard of, and what he has learned himself. Check out some of his incredible photos in the slideshow above. RE: I bet a lot of people ask you what your favourite country is. Does it drive you crazy? RM: It's pretty much the most common question. And the less travelled people ask it even more. And my typical answer is: It depends. Are you interested in culture, history, nature, landscapes, people, food? And so on… RE: Travel is so personal. I always tell people, “just because I had a great time in X, doesn’t mean you will.” Perhaps folks just want reassurance. I do like throwing in amazing countries they wouldn’t have thought of much, like Sri Lanka, and Cook Islands. RM: I do the same and go a step further - Mauritania, Greenland, Turkmenistan, Iran, Vanuatu. See how their eyes open wide in disbelief. Djibouti as well. RE: At this point, you could just start making names up! I’ve got a text box in my new Global Bucket List book about the amount of countries in the world. “The United Nations currently has 193 members; the US State Department recognizes 195. FIFA has 208 members because it takes into account countries that are governed by other countries but can still kick a soccer ball. Most sources give the number at 196.” How do you define a country? How many are on your list? RM: I have my own list of countries. To me a country is not a UN entity but more like a unique destination - with it's own culture, nature, people, history, geographic isolation, and its own government. You start with a UN list, add various former colonies and islands and territories, add a bunch of de facto independent countries and you get close to 300. Greenland, Cayman Islands, Transdniester, New Caledonia, Galapagos, Easter Island, Canary Islands - these are all countries to me. Here’s my full list of countries. RE: And is your goal to visit all of them? RM: Not the primary objective. I am interested in seeing the most incredible and unique places in the world, having incredible experiences while doing it, and meeting people from all over the world. Plus I like contrasts - one day you are trekking Rwenzori Mountains in Uganda, next week you are in Norway seeing Northern lights, next week you are clubbing in NYC and next week you are in the South American jungle. I am also still trying to see every possible animal migration and mammal species there is. RE: I found the richness of the experience can become overwhelming, like eating too much dessert. How do you keep it fresh? How do you prevent becoming a jaded traveller? RM: Alternate the experiences. When I got to "chateau-ed out" in France, I went hiking in Pyrenees. When the Western European democracy gets under your skin - you try Russia or Egypt. RE: I’m sure many readers will be asking themselves: how the heck does this guy afford it? Were you a Wolf on Wall Street? Do you have to make personal and professional sacrifices to travel with such dedication? RM: The fact is that travelling is actually often cheaper then living in a big metropolitan city. In many countries you can survive on $50 per day in relative comfort. The biggest expense of travel is airfare - which you minimize of you country to neighboring country, or allow for flexibility in finding cheap flights. You could lease a car in Europe for a long-term lease as cheap as 20 euro a day. South America, Asia, Middle East are all relatively cheap. Professionally it's definitely a huge sacrifice - but I’d rather look back at my life and think about incredible experiences than stare at a bank account or remember sitting in front of monitors and watching markets oscillate. RE: Oscillating in Transdniester. That’s a good title for a book. And I confess I’d never heard of Transdniester until you mentioned it! RM: In Transdniester you actually experience time travel. It's like going back to USSR - Lenin statues, rubles with hammer and sickle on them, beer in metal barrels sold in the streets. It's a completely independent country with its own government, money, military and police, language, sports teams. Just not recognized by UN RE: I just looked it up on Wikipedia just in case you were making it up! OK, so what country did you find the most welcoming, and what country was the most hostile? RM: For the most part I have to say that pretty much every country is welcoming. You always meet people who are proud of their country and want to show it to you. Iran was probably the biggest surprise in how open and friendly people were. Same for Cuba. Slovakia, Rwanda, the Pacific Island nations, Central Asia. Different culturally, definitely, but open arms everywhere. Perhaps maybe the Gulf Countries were a bit stuffy. But so are some states in USA. RE: Have you noticed any universalities among the nations? Is globalization as prevalent in the cultural sense as the media would have us believe? RM: Well, there’s cell phones. No matter how poor or isolated the country is - everybody has iPhones or smart phones of some sort, and most places have wifi. It was easier or find wifi in Egypt then in New York. RE: Even in Transdniester and Djibouti? RM: Transdniester absolutely. Djibouti, in the capital city. When I was camping in the desert, not so much. RE: You’re chasing migrations and mammals too. What’s your favourite mammal? Some of them can be quite elusive. Like the virtuous and honest politician (or so I’m told...) RM: I haven't met a virtuous and honest (or even either/or) politician yet. In the animal world - gorillas, orangutans, whales, grizzlies, elephants, lions are much easier and more enjoyable to deal with. RE: You take some incredible images (some of which I’ve used in my books). Do you have a favourite? The pic that always brings a smile to your face? RM: My top 3 stunning places, visually: Danakil in Ethiopia, Kamchatka in Russia, the Icefjord in Greenland. Most pictures bring incredible memories. That's the beauty of travel. Every country and city gets a real feel and taste and color, rather than just being a name on the map. Some of my favorite pics were from most insane experiences - like hugging a white baby seal in Canada, standing on top of Mt Kenya, stretching my arm toward a gorilla or whale shark, dancing my ass off in Ibiza during fluorescent spray-paint night. It's an endless list really. RE: So, you travel around the world. What have you learned? RM: Be open to other people and their views of life; be respectful of their cultures and traditions; try every food you can; take on all physical challenges; learn about everything and anything. Enrich yourself with knowledge and experiences, and then continue to repeat the process. The sky truly is the limit. RE: I totally agree. And what’s next? RM: A small trip to British Virgin Islands, then back to New York for DJ classes. And then: West Africa, Polynesia, Mongolia, India, more of Brazil and Russia

Every year, a research organization named Skytrax surveys millions of passengers around the world to come up with the definitive list of the World’s Top Airports. It’s ranking looks at 39 different airport services, based on reviews from over 11 million people travelling through 240 airports. There’s dozens of categories for Most Improved, Low Cost, Continents, Shopping etc, but no Worst Airport, so I added that myself. Changi Airport, Singapore Clearly, Singapore understands that passengers want more from their airport experience than being herded into gates like cattle, frisked like terrorists, and fed stale overpriced sandwiches stuffed with mystery meat. Changi’s free amenities (free being a defining factor) include internet, massage chairs, and a cinema to help pass the time during unexpected delays. Pleasing aesthetics come in the form of waterfalls, green spaces, even a butterfly garden. Clean, and efficient, Changi is currently rated the world’s best airport. Incheon International Airport, South Korea South Korea has been competing with and often outpacing their Japanese neighbour’s economy, automobile industry, and airports too. Incheon runs like a finely tuned, well oiled machine. Surgically clean and easy to navigate, survey respondents made special mention of the friendly and helpful service, along with amenities like showers, where passengers can rent towels for just $2. There’s an affordable transit hotel located in the airport itself too, and of course free internet, something most major US airports feel need to charge/fleece you for. The survey awards points for immigration and customs, and Incheon leaps ahead here too, with line-ups whizzing through Munich Airport, Germany Munich tops the list of Europe’s Best Airport, ranking 3rd overall in 2014. Survey respondents enjoyed contrasting it to Frankfurt, which falls further down the list, although one would assume smaller airports are easier to manage. How about free coffee or tea and a newspaper with your Bavarian sausage? A nice touch appreciated by passengers travelling in economy. The airport’s modern interior is elegant yet functional, good signage, with all the efficiency you’d expect from a German airport. Hong Kong International Airport, Hong Kong Hong Kong is one of only three 5-star rated airports, the other being Changi Singapore and Incheon in South Korea. Is there a coincidence that the three highest rated airports are in Asia? In the movie Up in the Air, George Clooney makes a stereotype that one should always get in lines with Asian passengers, who are efficient and move quickly through the system. No surprise then that Hong Kong is praised for its efficiency through the gate, check-in counters, even security. It also got full marks for having views of the runways and planes, a great selection of food options, public transport, cleanliness and, being Hong Kong, excellent Duty Free shopping. Zurich Airport Leave it to the Swiss to make everything run like clockwork. Zurich is prized for ambience and views, service, information and public transport to and from the airport. Yes, apparently you can set your watch to the train schedules. The self-service check in machines offer 15 languages, the toilets are spotless. Bare in mind, when the signs say it will take you 12 minutes to walk to your gate, they mean it. Vancouver International Airport, Canada YVR proudly remains the Best Airport in North America, cracking the Skytrax Top 10 list dominated by Asian and European terminals. I personally believe it belongs in the Top 3, but that might have something to do with the fact that YVR is my home airport, and is always a pleasure to return to. Renovations for the Winter Olympics helped create a spectacular bright space, complete with First Nations Art, water ponds, and new, reasonably priced restaurants. I feel a great deal of pride watching passengers ogle at the giant fish tank, with its luminous floating jellyfish, or the landmark Bill Reid sculpture in the Departures Hall. Free internet all around, and massive kudos for free baggage carts, in contrast to other major North American airports that feel compelled to nickel and dime passengers at every opportunity. My Worst Airport Experiences Africa’s three best airports are located in South Africa, still benefitting from renovations for the World Cup in 2010. My least fond airport memories lie elsewhere on the continent. In Addis Ababa, I waited two hours for my bags to show up, with no food, rank washrooms, and nobody knowing anything about nothing. The worst check-in chaos I’ve experienced was in Dubai, where Nigerian passengers overloaded with commercial goods practically stampeded anyone in their way. In Europe, I recall the hot Slovenian transfer shuttle that waited until the bus was jammed with passengers from the plane, and then drove ten metres across the maintenance road to the entrance gate. Ten metres! Security flagged me in Cairo for some reason, twice, and how could I forget Houston’s ridiculously long-winded double screening process, under the shadow of posters depicting the Twin Towers in flames? Travel is stressful enough folks. Give us somewhere clean to eat, freshen up, relax, and check our email without taking out a mortgage. Is that too much to ask?

You’ll find Doctor Fish in spas from Croatia to Singapore, Belgium to China, on the streets of Bangkok and Siem Reap. My own consultation was in Seoul, where several dozen little fish were gleefully dining on my feet. Literally, chomping down with gusto, hold the mayo, extra toe jam please. They’re called Doctor Fish, also known as “nibble” or “kangal” fish, although the scientific community calls them garra rufa. Originating in Turkey, these bottom feeders are sought the world over by sufferers of psoriasis, an icky skin condition. Reason being: they just love to to eat flaky dead skin cells, rejuvenating your feet in the process to leave them soft and shiny. Unlike piranhas, which have trouble distinguishing disposable edibles from your essential body parts, Dr. Fish have evolved to only nibble what you don’t need, attracted to dead skin, calluses, corns, and other delightful things you like to share with your neighbours in the local public pool. Although they don’t heal skin conditions, they are known to relieve the symptoms. Lord knows I’ve eaten enough fish in my time, so it was time to give something back to a species that has given me so much. Like many spas in Seoul, the Sea La La Spa and Waterpark is a haven of relaxation. There’s various types of saunas, dozens of jet pools, steam baths, pools, Jacuzzis, meditation rooms, even coffin-sized private caverns where you can slide inside and doze off free of distraction (unless you choose the caverns with the TV sets and DVD players). The Dr Fish pool is located at the back of the giant indoor pool plaza, and costs about $10 for a 15-minute soak. There are two ponds, one containing the garra rufa, and another containing a larger species of fish called Chin Chin. Although the spa claims both eat your dead skin, I subsequently learn that Chin Chin (or kissing fish) are impostors, nibbling away without actually giving any of the medicinal benefits. In fact, some experts reckon they could actually spread diseases instead, which makes sense considering they spend their days kissing complete strangers. I approach the garra rufa pond, sit down, dip my feet in the water, and wait for the feast. After an initial tasting by one bold fish (who must have been an important food critic), dozens proceed to munch away, selecting the heel, toe or underside the way we might select a cut of steak. The sensation is one third pins and needles, one third tickle, and one third “holy crap, I’m being eaten alive by tiny hungry fish.” It’s important to remain still, after all, we don’t like it when our dinner plate moves around either. When your time is up, your feet are left refreshed, radiant, free of excess dead skin, corns, and other itchy conditions you might find in a locker room. The Chin Chin in the other pool may not be real Dr Fish, but this species of tilapia actually have teeth, which means their bite is worse than their, em, blow? They approach my feet like bandits, and this time I practically hit the roof as they attack. I haven’t squirmed this much since I mistakenly told a Bolivian political leader his wife looked like goat cheese (it was a slight mispronunciation). Turkey passed a law protecting garra rufa from “commercial exploitation” over fears of they’d be exploited, but it’s not as simple as filling your bath tub with the fish to start a spa. Conditions, ranging from water temperature to diet, have to be ideal before the garra rafa will want to feed on your scales. I once knew a real Dr Fish, and I was mentally spiralling out of control at the prospect of a dermatologist named Dr Fish treating his patients with Dr Fish.

Click. I stood on the landmine, about the size of a can of pop, a container made of lightweight plastic like cheap toy soldiers. I always thought landmines were disk shaped, and that if you could replace your weight, you might slip away unharmed, at least according to Hollywood. “No, you hear click, you explode,” says the Cambodian volunteer guide. The last click you’ll feel with your legs intact, if you survive. Fortunately, this landmine was disarmed, one of the thousands on display at the Landmine Museum outside Siem Reap in Cambodia. The trigger device still worked, so standing on the lid, no bigger than a garden sprinkler, it still had the impact of pulling the trigger of an unloaded gun, aimed directly at my head. After the U.S invasion during the Vietnam War, the blood-drenched rule of Pol Pot, and the decades of civil war that followed, Cambodia is one of the most mined countries on the planet. An estimated five million mines are still to be found, many by wandering animals, farmers, and children. It is estimated that one out of every 290 Cambodians is a landmine victim. In the game of war, landmines play dirty. They are cheap to make, easy to camouflage, designed for maximum carnage and injury, and patiently hide long after the war they were deployed for is over. Built in a variety of shapes and sizes, landmines do not have a sell-by date. As Cambodia rebuilds itself in a new century, the weapons of the past continue to maim the innocent. Aki Ra’s life mission is to put an end to this, one dangerous mine at a time. Photo: Landmine Museum A former child soldier of the Khmer Rouge and later the Vietnamese Army, Aki Ra was laying landmines in the jungle before he reached his teens. Cutting trails in the jungle, he would lay traps, mines and trip wires, carefully camouflaged with soil and foliage. One mine might trigger another so that a single careless step could wipe out an entire platoon. Claymore mines, detonated by tripwires, are loaded with ball bearings that fire in every direction, causing massive harm to anything in the vicinity. US-made Bouncing Betties have a spring mechanism that shoots it up to head height before it explodes, resulting in maximum carnage. Aki Ra was told to lay them all, Chinese pineapples, Russian mines made of wood, salad-bowl anti-tank mines. Today, his Landmine Museum, 25kms away from Siem Reap and Angkor temple complex, is a disturbing glimpse into real-life horror, and the human spirit that defies it. Privately funded without government aid, Aki makes frequent trips into the jungle to disarm the devices that continue to torture his country. He estimates that he has removed some thirty thousand mines, an incredible feat given the fact that Aki doesn’t use modern mine detecting equipment. Drawing on his childhood knowledge of where to hide mines and how best to disarm their fuses, his success rate, and survival, is incredible. It costs about $500US for an aid organization to remove a single landmine. Over 130 countries have banned the use of landmines, but major arms manufacturers like the USA, Russia and China continue to produce and distribute mines for as little as $3 a unit. The human cost is incalculable. Aki’s museum has adopted about a dozen young landmine victims, missing arms and legs, but making up for it in spirit. They help out at the museum, and a village has sprung up around the museum since Aki successful cleared it of mines in the early 1990’s. Inside a small hut, hundreds of mines are on display, along with information as to how they work and where they are found. A video runs showing Aki walking through thick jungle, the cameraman literally shaking for fear of taking a wrong step. “Look at this small field,” asks the guide. “How many mines can you see?” It’s the size of a vegetable patch, and I can just make out a trip wire connected to a mortar bomb hanging from a branch. I count four mines before he begins to point them out. There are dozens - in the ground, behind leaves, attached with gut-wire above my head. Some are only designed to blow off one leg, others the entire lower torso. You wouldn’t stand a chance. Photo: Landmine Museum After the gunpowder has been “steamed” out and the mine is declared safe, Aki displays them in his museum to educate people about their continuing danger in Cambodia, and the world over. On the video, a one-legged survivor kid who lives at the museum scores a goal in a friendly soccer game, his spirit inspiring. The TV is turned off. Click. The Landmine Museum relies on visitor donations and volunteer help. Entrance is free, and English-speaking guides are available by donation. More info at www.cambodialandminemusuem.org

Sometimes, things don't go exactly as planned The Bus Ride from Tirana to Dhermi, Albania It was supposed to take four hours, but it took eight, and every of them was an attack on my shattered nerves. The bus, possibly held together by elastics, could barely make its way up steep mountain hills, while rusted springs stuck through the vinyl seats and poked in my butt (think marshmallows on a sharp twig). The driver’s buddy thoughtfully came around to collect all the trash, and promptly through it out the window. The surface of Mars is in better condition than most Albanian highways, but that didn’t stop the driver from playing chicken with the approaching trucks. Wrecks lined the road to prove head-on collisions were common, just in case I thought he knew what he was doing. The Flight from Addis Ababa to Lalibela, Ethiopia While we’re in Africa, lets check into the only flight I’ve ever been on that broke down mid-flight No sooner had we taken off from one of many stops along the way than the twin prop Fokker pulled a U-turn and landed back on the runway, the result of engine/wing/equipment/something trouble. Four hours later, another plane arrived, also experiencing technical difficulties. The passengers from that flight transferred over to our plane, which all of a sudden worked, and took off, leaving us still on the tarmac. Another four hours later, another plane arrived that may or may not have been in working order, but since it was a choice between a night on a runway or arrival amongst legendary 11th century rock churches, survival seemed like a small price to pay. The Tazara Rail from Kapiri Mposhi to Dar es Salaam It’s one of the great African train adventures, 38 hours through scorched wilderness. Sounds great, now lets crank the heat, overcrowd the cabin, blast bad music through distorted speakers, obscure the windows with thick layers of dust, cross the wildlife reserves at night when you can’t see anything, charge $10US for soggy eggs that nobody in their right mind would eat, and depart once a week (maybe) from a train station that is only slightly cleaner than an open pit toilet after a school trip. Not that I’m complaining. The Rickshaw in Puno, Peru Pedal-power rickshaws can be a charming, cheap way to get around bustling cities in the developing world. In the southern Peruvian town of Puno, the driver is located behind the carriage, as opposed to the front of the carriage in India, or the side, as found in Malaysia. My rickshaw took a corner and the carriage suddenly came to an abrupt halt. I turned around and saw my driver had somehow lodged himself underneath a car. How he did this is beyond me, as it quite possibly defied the laws of physics. The rickshaw rider seemed OK, especially after he received a wad of notes from the car’s frantic driver. I hopped into another rickshaw, but insisted the driver get in the carriage so I could pedal off safely myself. The Train from Rishikesh to Chakkebank, India Having waited two hours in a steaming carriage before the departure, I was exhausted from fending off beggars, and a maniac selling hot chai. Finally, we left the station, travelled ten minutes through an open sewer, stopped, and spent another two hours waiting for Godot. Due to a festival, the second-class sleeper carriage was crammed with people. I dozed off on my top bunk and woke up to find two guys sitting in the gap between my legs. When a third guy tried to join the party, I put my foot down, literally, on his head. The Slow Boat down the Mekong River, Laos The 48-hour slow boat resembles a long, wooden coffin, which is why I felt like death after the journey. The engine is deafening, the wooden seats narrow, providing ample legroom for five-year old dwarfs. Noise, heat, splinters, smells - it’s almost, but not quite, enough to spoil the incredible views I passed along the way The Ferry from Salvador to Morro de Sao Paulo, Brazil Serious ocean storms are nothing to be sniggered at, even in a large catamaran designed to pounce over huge swells. On this 90-minute ferry ride, I had two choices. Go outside, get soaking wet and hang on for dear life, or stay inside and fill up a barf bag with yesterday’s beef stew. It felt like the Perfect Storm, with more fear, and no life jackets. Inside, the puke was gushing up and down the aisles. The Metro to Budapest Airport, Hungary With a terrible hangover, I had two hours to get to the airport for my flight from Budapest to Istanbul. Due to construction on the metro, I took a bus shuttle to the nearest station, which locals informed me was complimentary. Not according to an overzealous ticket inspector, who let me off a considerable fine after much begging, but still confiscated my remaining metro ticket in spite. Nervously, I rode the metro without a ticket to the last stop, only to realize I had gone in the wrong direction. Time was ticking, my head was exploding. All the way back in the opposite direction, I arrived just in time for the airport shuttle driver to slam the door in my face. I just made the flight, with no help whatsoever to the Budapest transit system along the way. The Arctic Night Bus in Sweltering Brazil Night buses are my bane, but often provide the only way to get from A to B. What made this bus special was the driver cranking the air-con so high that icicles were forming on the edge of my nose. Outside, it was a warm and pleasant tropical evening, but inside the bus, the Arctic Circle was blowing a snowstorm. With all my gear inaccessibly packed way in the storage beneath me, I was only wearing shorts and a T-shirt, spending the long, painful night shivering and shaking. The only advantage to all this was being able to flick the frozen mosquitoes off my legs. Originally published on Sympatico.ca

|

Greetings.

Please come in. Mahalo for removing your shoes. After many years running a behemoth of a blog called Modern Gonzo, I've decided to a: publish a book or eight, and b: make my stories more digestible, relevant, and deserving of your battered attention. Here you will find some of my adventures to over 100 countries, travel tips and advice, rantings, ravings, commentary, observations and ongoing adventures. Previously...

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed