|

Canadians know that any country sitting in the shadow of a more popular neighbour is often overlooked. Spare a thought for Slovenia, that small nation in Central Europe within sight – quite literally – of Italy, Austria, Hungary and Croatia. While international visitors to Europe might beeline to nearby Venice or Milan, Salzburg, Budapest or even Zagreb, many would be hard pressed to locate Ljubljana on the map, much less be able to pronounce it. Slovenia lacks the attention of its more famous neighbours, but discovering its historical capital, frosted peaks, glimmering lakes and lush countryside, it’s clear this modest nation can compete with all of them. With its central location and abundant natural beauty, Slovenia was considered a prize territory for the conquering armies of Rome, Austria-Hungary, Croatia, Germany, Serbia, Italy, and finally, the Communists who incorporated it into Yugoslavia. Claiming its independence with an impressive lack of political turmoil in 1991, Slovenia officially joined the European Union in 2004, adopting the euro but keeping its identity intact. The nation of two million people has quietly got on with the business of becoming one of the most prosperous, stable, and successful of all the post-Soviet states. It frequently ranks among Europe’s best economies, scores big in lifestyle indexes, and it really wants you to not confuse it with Slovakia, a different (and take it from me, less impressive) country altogether. As I wander the streets and canals of old Ljubljana (say it with me: Yoo-bli-yana), I’m reminded of Copenhagen, Stockholm and Budapest. Yet Ljubljana feels cleaner and more civilized than those capitals, immaculately maintained with arty cafes, old world architecture, copper Church steeples, ample bike lanes and manicured parks. Locals roam about, stylishly dressed in that casual, modern European manner of looking fantastic without much effort. I take care not to trip on the city’s polished cobblestone for fear of cutting myself on those striking Slavic cheekbones. Students bike across the Games of Thrones-ish Dragon Bridge and distinctive Triple Bridge, the public art is impressive, and even the urban graffiti is tasteful. Overlooked by the 900-year-old Ljubljana Castle, the capital is a template for any great European capital, with half the tourists. I expect to find more visitor’s at Slovenia’s premier tourist attraction, historic Lake Bled. Sitting at the foothills of the towering Julian Alps, you might have seen images of the lake on screensavers or Instagram or any platform hoping to illicit a ‘wow, where the hell is that?’ response. It had taken me less than an hour to drive the smooth highway from Ljubljana, and ‘WOW’ got cap-locked when Lake Bled came into view. Framed by mountains and thick forest, the placid, emerald-coloured water has a small island in the centre with a notable European landmark. The gothic Church of Mary the Queen was first consecrated in the twelfth century, and restored to its current state in the seventeenth century. “Europe,” as Eddie Izzard remarks, “where History comes from.” Long before the island became a site of Christian pilgrimage, it was a cult centre for Slavs to worship the Goddess of Love and Fertility. Fittingly, couples flock from around Europe for destination weddings in one of several grand lakeside hotels, the remains of former royal palaces. Tradition holds that grooms must carry their bride up ninety-nine steps to the chapel, and ring the famous bell three times for good luck. Judging by the strain I see on the flummoxed faces of several men, carrying anyone up ninety-nine steep steps and then ringing a heavy bell is more difficult than it appears. The rest of us will just fall in love with the warm, azure water, four-hundred-year-old rowboat transportation (called pletnas), lovely ambiance and a location so striking you’d think it had been airbrushed onto the cover of a romance novel.

Visitors to Slovenia often complain they should have allotted more time. More time to explore the notably affordable all-season mountain resorts. More time to hike, fish, bike, raft, and enjoy the country’s abundant outdoor splendor. More time to visit Lipica, the ‘cradle of the race’ of the unicorn-white Lipizzaner horse that have dazzled dressage events for centuries. More time for show caves, the world’s deepest underground canyon, the robber-thief Predjama Castle, or visits to old churches and abbeys. The country is compact and easy to get around, English is widely spoken, and the local cuisine draws heavily on the best traditions of its neighbours: outstanding beer influenced by Hungary; pizza, gelato and coffee by Italy; schnitzels and pastries by Austria.

Yes, we know all about living in the rain shadow of a more famous country that soaks up the world’s attention. This is why Canadians will particularly appreciate that quiet, overlooked and underrated Slovenia might just be the most enticing country in all of Europe – east, west, and otherwise.

0 Comments

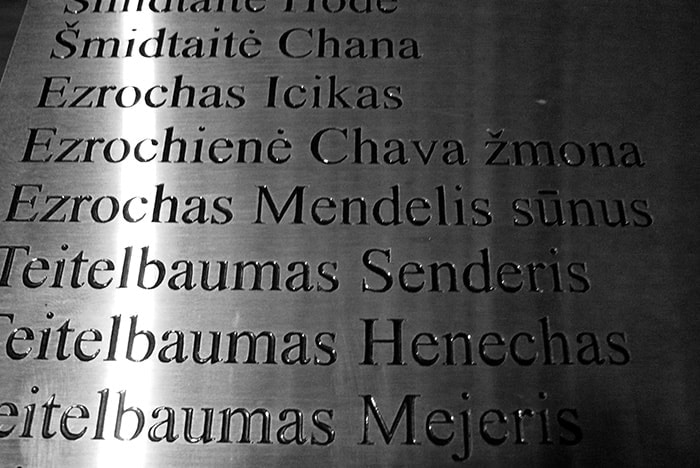

Bucket Lists are so much more than places to see and things to do. They can teach us about the world we live in, our place within it, who we are, and where we come from. Whatever nationality you’re descended from, visiting the country of your ancestors results in rich, emotional travel. Genealogical tourism first exploded in the 1970’s, largely credited to the success of Alex Haley’s book (and subsequent television series) Roots. With the evolution of online genealogy tools - designed to make databasing and research as simple as ever – it has now become one of the busiest traffic segments online. Dedicated and enthusiastic volunteers become private investigators of their familial pasts, looking for unlikely connections, unusual stories, and answers to questions of their origins. If you think social media is addictive, try looking into your own lineage. Genealogists advise to start with what you know. I know my grandfather was born in a small village in northern Lithuania called Kupiskis. Before booking a flight to the Baltics, I hit up the All-Seeing Eye of Everything (aka Google) and found a wealth of knowledge. Kupaskis, like all shtetls in Europe, has a tragic history. Before World War II, forty-one percent of its population were Jews, all of who were rounded up and brutally murdered by local Nazi collaborators. Over three thousand men, women and children were massacred, including members of my own family. While many people travel to the countries of their heritage expecting to encounter long lost relatives, there is no chance of physically discovering a forgotten branch of my own family tree. Despite this, I headed off to Lithuania, eager to see what else I might discover. Vilnius is a lovely European capital, with big town squares, cobblestone, cheap beer, few tourists, and welcoming locals. It’s a three-hour drive from the city to Kupiskis, which is no longer a shtetl, just a small industrial town. Piloting an old rental van, the surrounding countryside explodes in the colours of fall. Each passing kilometre is one more step into the past. A bold sign on the outskirts signals I have arrived in the town. I feel like a grown turtle washing ashore on the very beach on which I was hatched. In 2004, a group of fifty Kupiskis descendents from as far away as the US, UK, South Africa, Denmark and Australia visited this small town to dedicate a memorial to the Jewish families wiped out in the war. They were greeted by the town mayor, and presented with a list of the names and ages of the victims compiled by a local midwife during the war – the only such list that exists in the country. These names are now engraved on a memorial on a plaque on the old synagogue, which is now the town’s library, and my first stop. I run my hand over the names on the memorial, stopping at several with the surname root of Ezroch. It is exhilarating to meet the names of these ancestors, and depressing to know what happened to them. I’ve found and lost new family members all at once. Late afternoon Kupaskis is half asleep, the streets deserted. Red and gold leaves cover the roads. Some locals still get around in a horse and buggy. There are a few clues of the town’s rich Jewish history; the old library, and a street named Sinagogo, still lined with century-old old wooden houses. It is cold and damp, and I wonder how my great-grandparents adjusted to the hot, dry veldt when they immigrated to South Africa before the first World War. I wonder what might have been if they didn’t. With the help of a local guide named Regina Kopilevich, who specializes in genealogical tours, I visit several mass graves, some of them with memorials, some of them with vandalized plaques. Who would deface a mass grave? The same kind of person responsible for its existence in the first place. Jews and Gentiles had co-existed peacefully here since the 16th century. Regina leads me to the ancient, wooden house of a 91 year-old local woman named Veronica. Floating in and out of lucidity, she recalls babysitting Jewish children, even singing me a few Yiddish lullabies from the depth of her memory. Her house overlooks the Freethinkers Cemetery, a nearby site of one of the worst massacres. Veronica witnessed the children in her care stripped, lined up, and murdered. “I still see their faces,” she says, “I cried and cried.” The room is freezing, as if all the joy in the world has been sucked right out of it. Veronica died a few months after my visit, taking those lullabies and horrors to her own grave.

Watch an extended clip of my visit to Kupiskis while filming my TV show, Word Travels Back in Vilnius, I spent hours researching life in Kupiskis, reading old reports, and the testimonials of survivors. I Skyped my grandmother in Johannesburg and asked questions, feeling somewhat disappointed in myself that I had never asked her these questions before. In turn, she was fascinated by what Lithuania looks like today, what has become of Kupiskis, a place that always haunted my late grandfather. Lithuania’s history did not settle. First the evils of Hitler, then Stalin, it became the first Eastern Bloc country to declare its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Although my own roots were dug up, I’m nevertheless drawn to country, its under-the-skin familiarity. Three of my four grandparents were Lithuanian. It must count for something. Michael, a distant cousin in New York, is an amateur genealogist and proved a great resource prior to my visit. He amassed over three thousand names on my family tree. I asked him how others should begin their personal journey. “Talk to your parents and the oldest people you can find in your family. Ask them very specific questions. Names of places, birth dates, if they have any newspaper clippings,” he told me. Every time an elder family member passes away, they take with them an important piece of the puzzle. Genealogical travel brings the rewards of travel you’ll find anywhere: beautiful landscapes, interesting new cultures, people, food, and history. Yet when you journey into the land of your heritage, it makes those rewards all the more relevant. You don’t need plane tickets or hard earned savings to begin your quest either. If you’ve ever wondered about where you come from, your Bucket List simply wants you to start asking questions. Note: There are thousands of volunteer genealogical societies worldwide who can help you start your search. Websites like Cyndis List and JewishGen contain many links to get you started, and there's all sorts of software to utilize. Talk to the people you know before going to online archives, census records, obituaries, newspaper clippings, and other sources of information. It is highly likely you’ll soon encounter a relative or enthusiast on the same path, eager to share and learn from you. Remember, when publishing personal information on websites and databases to respect others privacy.

East German Cars Once Patrolled the Berlin Wall Threatened to Mow Down Escapees with Laughter Berlin’s dark days are thankfully history, but the city continues to attract tourists fascinated with its Communist past. Checkpoint Charlie, the Berlin Wall – it’s difficult to imagine that just two decades ago the city was a major Cold War battlefront. Patrolling the lines was an East German car called the Trabant. Built between 1957 and 1990, the Trabant (or Trabi) was a vehicle that epitomized life under Soviet rule. Ugly yet reliable, the average East German citizen would have to wait around 13 years before they could acquire a Trabi, and forget about choosing the colour. With hardly any production changes in its history, the Trabi used a unique gearbox and an engine reliant on gravity to deliver fluids to the right places. Famous for its choking exhaust, it could hit a top speed of 112 km/hr (downhill) and seat four comfortably (provided circulation in your legs was a non-issue). East Germans used to joke that the quickest way to double the value of a Trabant was to fill up the petrol tank. Over three million of these cars were produced, of which around 58,000 survive, largely in the possession of collectors. Today, a company named Trabi Safari offers tourists the chance to explore Berlin at the wheel, driving in convoy with a guide in the lead car pointing out interests over short-range radio. I would have liked to hear more, but I was too busy riding the clutch as I tried to work the gearshift, which works on the principle that anyone who drives a Trabi will have no need whatsoever to drive a real car. Pull up, pull down, push in, push out, and somehow the car lurches forward as Berlin’s downtown pedestrians and drivers stare in amusement. “When you hear people use their horns, it’s because they either love Trabis, or hate Trabis,” explains our guide. Or maybe it’s because I almost crashed into them, who knows? Trabi Safari’s cars are painted in bright retro colors (the better for locals to see them and take evasive action) and the company gives ample instruction on how to drive the car. It’s all a very tongue-in-cheek affair, from the guide’s comments as quirky as the cars themselves. It’s hard to believe that East German border guards used to patrol the no-go zone in Trabis. Perhaps the plan was to stop escapees with laughter. My bright blue Trabi followed a bright pink one, and with the yellow customized convertible Trabi trailing behind we looked like an Eastern European remake of The Italian Job. When a new Mini drove past me, it actually dwarfed my vehicle. Driving into rush hour traffic, we passed the Reichstag, Book Burning Square, Brandenburg Gate, and more than a few unimpressed drivers caught in our wake. Incredibly, Trabi Safari has had almost no accidents, since local drivers know better than to assume tourists know how to drive one. Along the Berlin Wall, an iconic piece of graffiti shows former Soviet and East German leaders Leonid Brezhnev and Erich Honecker passionately making out at the wheel of a Trabi. As a symbol of popular culture, Trabi’s have appeared in everything from U2 videos to just about any Cold War spy movie. I was finding it increasingly difficult to put the car in the gear, much less believe that the model I was driving was from 1989. Need air conditioning? Open a window. The Trabi’s exterior is made from a plastic resin, supported by wool and cotton. In the event of a head on collision, accident victims can wear the car on the way to the hospital. “All Trabis go to heaven, because they’ve already had hell on earth,” crackles the guide on the radio. Then I fall behind so only pick up random words like “Nazis” and “Sexy Legs.” The tour continues towards Alexanderplatz, along Karl Marx-Allee, with its impressive and towering Soviet architecture. These buildings are fiercely grand, built by the Communists as a permanent reminder of the power of the state. All anyone had to do was get behind the wheel of a Trabi to see that the real power of the state was a smoky two-stroke engine that backfires. As a fun vehicle for exploring Berlin however, the Trabi is just perfect.

|

Greetings.

Please come in. Mahalo for removing your shoes. After many years running a behemoth of a blog called Modern Gonzo, I've decided to a: publish a book or eight, and b: make my stories more digestible, relevant, and deserving of your battered attention. Here you will find some of my adventures to over 100 countries, travel tips and advice, rantings, ravings, commentary, observations and ongoing adventures. Previously...

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed